In Focus: A darker side to globalization

29 OCT 2018

The Economist Intelligence Unit is at the forefront of global business intelligence. As the research and advisory arm of The Economist Group, the EIU specializes in providing insights into the world’s most pressing economic issues. In July, the EIU released The Global Illicit Trade Environment Index. The whitepaper ranked 84 countries on the extent to which their policies either inhibit or enable illicit trade.

While illicit trade is traditionally thought of as a law enforcement issue, the economic impact is severe. The whitepaper’s findings point out that the root causes of illicit trade are also economic. STOP: ILLEGAL caught up with The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Chris Clague to dig deeper into the thinking behind the index and some of the key findings.

STOP: ILLEGAL: Why is the EIU interested in illicit trade?

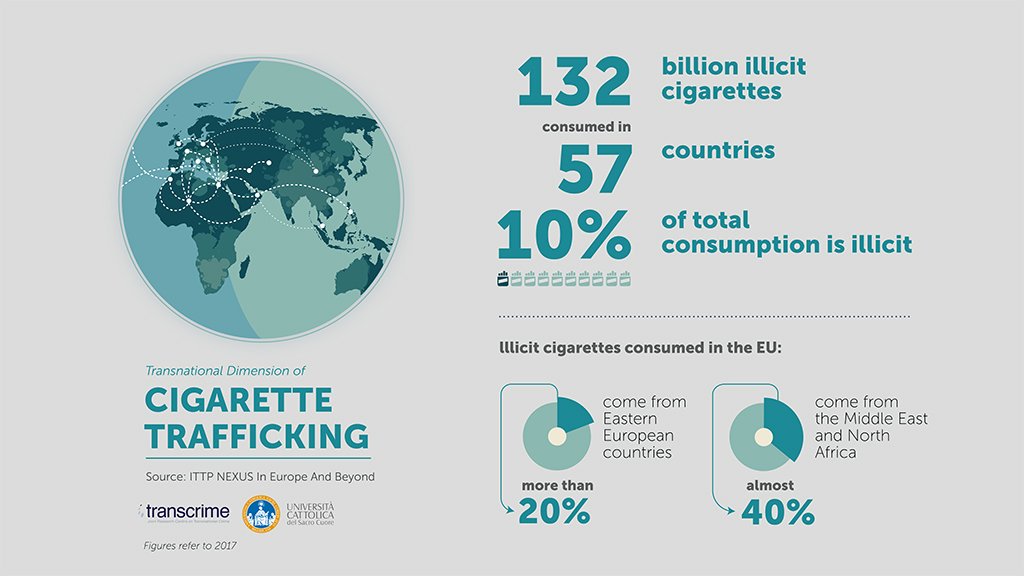

Chris Clague: At the EIU, we research issues that relate to many of the key themes you read about in The Economist. Trade, globalization, the political economy, development. While it often isn’t written about explicitly, illicit trade is a part of all of these. From the refugee crises across the Mediterranean, where chaos is providing cover for human traffickers, to North Korea, an economy which could not survive if it didn’t trade in arms, illicit cigarettes and counterfeit currency. Illicit trade is part of almost every geo-political story you read about in the news.

Historically, illicit trade has been present wherever there is legal trade. As the global economy has become increasingly connected, the reach of counterfeiters and smugglers has greatly expanded. The impact that this is having on the legal economy is significant. Fakes and counterfeits are what most people think of when they think of illicit trade, but there is also drugs, arms, human trafficking, and wildlife trafficking–all of which have been facilitated through greater global economic integration. Countries across the world have not done enough to address the downsides of globalization.

STOP: ILLEGAL: Why is an index like this important?

Chris Clague: The fact is that illicit trade funds transnational organized crime and international terrorist organizations. Pre-9/11, most international terrorist organizations received their funding through charitable donations and state sponsorship. That money flowed through the international financial system. After 9/11, the U.S., Europe, and various other financial centers around the world shut off that funding for terrorist organizations. So they had to look elsewhere to fund their operations and the obvious choice was to engage in illicit activity, whether it be counterfeits and fakes, illicit tobacco, sanction-busting oil shipments, human trafficking, drugs, small arms–these are the things that the public is not as aware of as they need to be.

Organizations such as the World Economic Forum, OECD, UN Office on Drugs and Crime, and various think tanks have all made estimates of the size of illicit trade. But the nature of illicit trade itself makes those estimates difficult as data is hard to come by. We felt that assessing the environment that countries create, either through action or inaction, would be more helpful. This can gain the attention of policymakers and stimulate discussion about what needs to be done to reduce illicit trade. Our index shows policymakers which levers they can pull on to better combat illicit trade. Some of these are well-known, but in a lot of instances there are many things that policy makers do not think about every day.

STOP: ILLEGAL: What are some of the main findings in the Index?

Chris Clague: One of the things that stood out most was the global disparity. Of the top ten countries with the most comprehensive anti-illicit trade policies, seven are EU members and the other three (Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) are among the top economies in the world. Their success is largely thanks to cooperation and partnerships between the European countries, as well as significant investment in border control and customs.

On the flip side, the five lowest ranked countries are some of the most impoverished in the world. Iraq, Libya, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia all face rampant organized crime and all lack the funds to effectively combat the flow of illicit trade. This enriches criminal organizations while causing more problems for their people and society. And thanks to increased connectivity and globalization, these problems spill over into both developed and developing countries across the world.

What this report really brings to light is that many governments aren’t doing enough to inhibit illicit trade. However, this is largely because they lack the resources to effectively tackle the issue. Globalization means that the issues that are affecting Libya will inevitably affect the European Union and the issues affecting Cambodia and Laos will impact the wealthiest East Asian economies. Illicit trade is a global problem and a global response is needed to properly tackle it.