In focus: The battle against organized crime, illicit profits and illicit tobacco trade

28 JUN 2018

Cathy Haenlein is a Senior Research Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), leading research on organized crime and illicit trade. Cathy is also Chair of RUSI’s Strategic Hub for Organised Crime Research (SHOC)—a platform established in 2014 with the support of the Economic and Research Council’s Partnership for Conflict, Crime and Security Research. The Hub brings together academics, policymakers and practitioners to create a true network of experts working together to improve the collective response to organized crime.

STOP: ILLEGAL spoke to Cathy about the latest trends in organized crime and illicit trade in tobacco.

STOP: ILLEGAL: How big an issue is illicit trade in tobacco?

Cathy Haenlein: Worldwide, illicit trade in tobacco and tobacco products is a major criminal enterprise. However, significant challenges exist around measuring the exact scope and scale of this activity. These owe to the often hidden nature of this form of illicit trade, plus the diverse forms it can take—from trade in counterfeit and contraband cigarettes, to illicit trade in component parts, loose tobacco, and counterfeit non-combustible inhaled tobacco products.

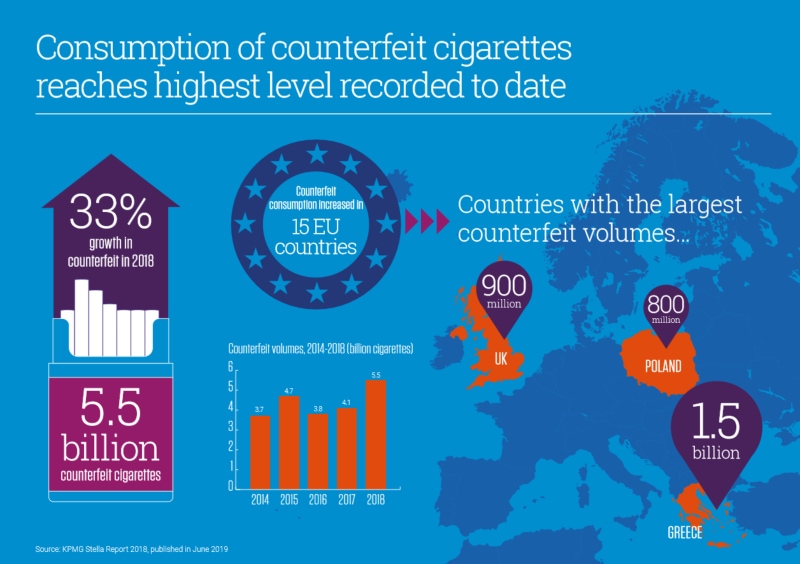

On the basis of empty pack surveys, in 2016, Project SUN calculated that over 48 billion illicit cigarettes were consumed in the EU, Norway and Switzerland, depriving governments of EUR 10.2 billion in tax. But despite these high levels of consumption, Project SUN also shows illicit cigarette consumption to be in decline. 2016 data represent a drop on 2015 figures, which show over 53 billion illicit cigarettes consumed across the same countries. This drop may be linked to reduced demand for illicit products alongside increased personal disposable income and reduced unemployment, as well as enhanced and targeted law enforcement activity in key locations.

However, even after this drop, illicit consumption continues to account for over 9 percent of total consumption, representing a substantial source of income for organized crime groups across Europe. While some opportunistic individuals may be active in this form of illicit trade, activity on this scale is dominated by organized crime on a transnational scale, run by agile, networked groups to feed ongoing consumer demand.

STOP: ILLEGAL: Does law enforcement take illicit trade in tobacco seriously enough?

Cathy Haenlein: Organized crime groups engaged in illicit trade in tobacco often face lower risks relative to other forms of crime. In many locations, this is because law enforcement has typically prioritized higher-profile criminal activity, such as drug trafficking, which is perceived to pose more immediate harm to citizens.

As such, illicit trade in tobacco presents substantial opportunities for organized crime groups: illicit cigarettes, for example, are cheap to produce and easy to transport, yet maintain a high sale price—driven by sustained consumer demand. The result is that profits can be just as substantial as those attached to higher-risk crime, whilst the risks attached to this activity remain lower.

As a result, many groups have diversified to exploit this low-risk, high-reward activity. Some have done so whilst continuing to engage in other crime types, shifting activities as potential profits and opportunities dictate.

In recent years, however, law enforcement responses have been stepped up in a number of locations. Significant seizures have been made, illicit cigarette factories have been uncovered and dismantled, and a growing intelligence picture has been developed on the groups involved. Yet new and evolving modus operandi continue to present problems for law enforcement.

STOP:ILLEGAL: Are there any new methods and routes that organized crime groups are using to smuggle goods?

Cathy Haenlein: The routes and methods used to move illicit tobacco are highly dynamic, evolving in response to shifts in law enforcement activity and potential opportunities.

One of the most important trends has been the growing use of online platforms, as well as postal services, to distribute illicit tobacco products. This trend is not limited to tobacco: postal services can be used to move everything from drugs to counterfeit consumer products, posing significant problems for law enforcement.

When dealing with postal services, a “little and often” approach is often used by illegal operators, whereby smaller consignments of illicit commodities are sent more frequently, in growing numbers. This approach challenges enforcement agencies’ use of thresholds to prioritize cases. The sheer number of parcels passing through the system places huge demands on enforcement efforts, requiring prioritization and the use of risk assessments. Yet “little and often” smuggling can allow packages to slip under authorities’ thresholds for investigation. The cumulative effect of this activity can be substantial, and the advantages for illegal operators are clear. Even if a consignment is detected, the small quantity of product intercepted can represent a minor loss against other parcels delivered successfully at the same time.

STOP:ILLEGAL: In your opinion, how important is public/private partnerships in tackling illicit trade globally?

Cathy Haenlein: The private sector has an important role to play in the prevention and disruption of illicit trade. This can take a range of forms, from providing support in assessing the authenticity of seized products, to collecting data on the overarching scale and scope of illicit trade, to taking the lead on improving preventative measures and technology to complicate efforts by organized crime to infiltrate legal supply chains.

Private companies can also cooperate at an operational level with law enforcement agencies. Industry intelligence, including analyses of legal sales, can offer valuable early indications of shifts in the illicit market. In many cases, the private sector conducts its own investigations into illicit trade, holding significant anti-counterfeiting resources, and a clear incentive to investigate cases to pass on to law enforcement.

Such public-private partnerships are all the more important in a climate in which organized crime groups are increasingly establishing, penetrating, and simulating legitimate companies to hide their illegal activities. Yet the extent of public-private cooperation varies across countries. In many cases, further efforts must be made to strengthen law enforcement–industry relations, to improve information-sharing processes and practices, and to widen the scope of joint initiatives.

For more information on Cathy’s work please see RUSI’s On Tap Europe country report on Italy.