Integrated Report 2019

| INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 |

The tobacco we source is cultivated in many regions of the world, including low- and medium-income countries, where it is typically grown on smallholder farms of less than two hectares. The socio-economic well-being of tobacco-farming communities depends on many factors, including the nation’s health and educational facilities, political stability, resilience to climate shocks, access to markets, and public infrastructure, as well as regulatory frameworks and their enforcement. If these factors are not present or are insufficiently developed, tobacco communities risk being locked in a cycle of poverty, which can lead to poor working and living conditions, including the use of child labor.

Topic description

For PMI, it means improving the capacity of tobacco-farming communities to achieve a decent standard of living, which is a key enabler to eliminating child labor and providing safe and fair working conditions on tobacco farms. Our strategy aims to ensure that contracted farmers achieve a living income, as insufficient income is often the root cause of child labor and other social and environmental issues.

Why it is important to us and our stakeholders

Poverty prevents farming communities from achieving acceptable levels of socioeconomic well-being and stifles local economic development. It leads to labor abuses and risk of child labor on tobacco farms because farmers may be unable to hire workers or afford school costs for their children, resulting in them keeping their children home to work on the farm. Child labor affects an estimated 150 million children worldwide, with the vast majority found in agriculture. It prevents children from getting a proper education, participating in the development of their communities, and fulfilling their potential.

Child labor and other such practices are morally unacceptable to PMI. From a business perspective, these practices also raise issues of compliance, such as potential human rights violations, and reputational risk. Tobacco is the main ingredient in our products, and a stable and successful farmer base is critical to ensuring the continuity of a high-quality tobacco supply. There is opportunity for us here, as well. As a global business sourcing tobacco from 24 countries, we can help address poverty and child labor through targeted initiatives and by developing strong working relationships with farmers, suppliers, civil society, governments, industry, and other stakeholders.

As with other agricultural commodities, the price of tobacco leaf and cloves can be influenced by imbalances in supply and demand, and crop yields and quality can be affected by variations in weather patterns, including those caused by climate change. Tobacco production in certain countries is subject to a variety of controls, including government-mandated prices and production-control programs.

Achieving our aims

A principal aim of PMI is to provide a decent livelihood to all contracted farmers in its tobacco supply chain. This has been a focus since we introduced our Agricultural Labor Practices (ALP) program in 2011. We are committed to the following set of targets to improve the socio-economic well-being of tobacco-farming communities:

Our aims

100%

Percentage of contracted farmers supplying tobacco to PMI who make a living income by 2025

Zero

Child labor in our tobacco supply chain by 2025

-

100 percent of contracted farmers supplying tobacco to PMI make a living income by 2025;

-

zero child labor in our tobacco supply chain by 2025;

-

100 percent of tobacco farmworkers paid at least the minimum legal wage by 2022;

-

100 percent of tobacco farmworkers provided with safe and adequate accommodation by the end of 2020; and

-

100 percent of farmers and workers having access to personal protective equipment (PPE) for the application of crop protection agents (CPA) and prevention of green tobacco sickness (GTS) by the end of 2020.

We use a risk-based approach to identify, prevent, and mitigate human rights– and labor rights-related incidents in PMI’s tobacco supply chain. We conduct our assessments using information on the prevailing conditions in the agricultural sector and what we have learned through years of internal monitoring and external assessments of our ALP program across our sourcing countries.

Our governance arrangements aim to guide and facilitate this work. PMI’s Senior Vice President of Operations, a member of PMI’s Company Management, is accountable for our success in this area, while the operational responsibility lies with the head of our Leaf Department. In each sourcing region, a management team oversees the implementation of ALP and has an established steering committee, which works closely with the dedicated local teams across our affiliates, as well as our suppliers.

Effective delivery of the ALP program depends on five core elements, which together help contracted farmers earn a decent livelihood, eliminate child labor, and achieve safe and fair working conditions. The ALP program is supported by related policies, such as our Good Agricultural Practices (GAP), our Human Rights Commitment (HRC), and our Responsible Sourcing Principles (RSP).

In 2018, we started a “Step Change” approach to our ALP program, focusing on four priority areas: eliminating child labor, ensuring payment of at least a minimum legal wage, the availability of PPE, and adequate accommodation for all farmworkers. Step Change focuses on resolving the root causes of these persistent issues in priority countries – which we assess periodically, and is run in collaboration with our partner Verité. The program focuses on Argentina, Mexico, Indonesia, Pakistan, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, and Turkey, due to the persistent nature of these issues there. A key component of the step-change approach has been to enhance external assessments and verification to support our progress toward our ambitious targets.

We are committed to a set of targets to improve the socio-economic well-being of tobacco-farming communities

Monitoring the implementation of our ALP program

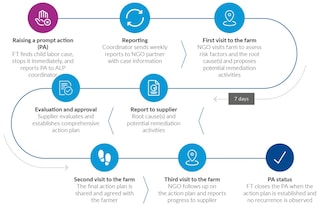

Internal monitoring: Systematic monitoring of the ALP program begins with the collection by field technicians of individual farm profile data, updated each growing season. The profiles capture key information about the people working and living on the farm, the size and type of farm, the number and categories of workers, housing arrangements, and school attendance. Field technicians then visit the farms throughout the tobacco‑growing season and evaluate, among other things, how well labor practices align with the principles of the ALP Code. “Prompt actions” are raised by field technicians to flag and trigger a response to any serious ALP violations. A remediation plan is then discussed with the farmer, followed up on, and monitored. If the matter is not resolved within the agreed timeline, it is further escalated. This may lead to sanctions, which can include contract termination in line with the due diligence and consequence management process.

External assessments: External third‑party assessments are conducted by Control Union (CU). CU evaluates the management system in place for ALP implementation, as well as the labor practices on the farms contracted by PMI and our suppliers. The assessment generally includes a review of prompt-action protocols and monitoring procedures. It also examines the internal capacity to implement the ALP program and understanding of farm practices, as well as how issues are being identified, recorded, and addressed. At the farm level, it assesses compliance with the measurable standards.

Focused CU assessments: Under our stepchange approach, we are implementing a specific assessment of the management systems in place relating to the stepchange priority areas, in addition to the farm-level ALP assessment.

External verification: The aim of third-party verification is to increase confidence in our internal monitoring data, as well as to improve the effectiveness of our program in addressing the targeted issues. Run on an ongoing basis, we use it to verify our understanding of progress on the ground, to challenge our monitoring data, to evaluate the effectiveness of our initiatives, and, ultimately, to better assess our impact. We work with local expert implementing partners in different geographies.

Child labor monitoring & remediation system

Despite persistent issues, which the program is proactively tackling, PMI’s ALP program is reaching a level of maturity and sophistication that we are proud of. To better share what we learn, and to receive ideas for how we can improve, we regularly participate in cross-sector events in which we detail our program experiences. In 2019, we also began to publish on our website ALP Progress Updates to share our experiences throughout the year, and we participated in various seminars and conferences on the topic, including a webinar organized by Sustainable Brands. Since 2000, PMI has been one of the early members of the ECLT foundation, a multi-stakeholder partnership that works to find collaborative solutions to address the root causes of child labor issues in tobacco-growing. PMI is strongly supporting ECLT’s efforts to provide a framework (the ECLT Pledge of Commitment and Minimum Requirements), which is based on ILO Conventions and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, for all members to align, reinforce, and where necessary, expand their policies and practices to progress in sustainably eliminating child labor.

Key definitions

A living income and a living wage are both about achieving a decent standard of living. A living income is the net annual income required for a household to afford a decent standard of living for all members of that household, such as self-employed farmers, whereas a living wage is applied in the context of hired workers (in factories or on farms, for instance).1

A minimum legal wage, as defined in PMI’s ALP Code, is a wage for all workers (including temporary, piece-rate, seasonal, and migrant) that meets, at a minimum, the national legal standards or formalized agricultural benchmark standards. An agricultural benchmark may be formalized where a minimum legal wage is not available or applicable to a specific context.

Child labor, as defined by the ILO, is “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development.” Under PMI’s ALP Code, the minimum age for admission to work is not less than the age at which compulsory schooling is completed and, in any case, is not less than 15 years or the minimum age accepted by the country’s laws, whichever age limit affords greater protection. No person below 18 should be involved in any type of hazardous work. In the case of family farms, a child may only help on the farm provided that the work is nonhazardous and light and the child is at least 13 years old or above the minimum age for light work as defined by the country’s laws, whichever affords greater protection.

Hazardous work means work that, by its nature or by virtue of when or where it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety, or morals of children or others. The following can, for example, be hazardous, particularly without the proper PPE: applying crop protection agents; stalk cutting; stringing; carrying heavy loads; working with sharp tools; working in extreme temperatures; and working after dark.

Green tobacco sickness (GTS) is a type of nicotine poisoning caused by the absorption of nicotine from the surface of wet, fresh, green tobacco leaves through the skin. The characteristic symptoms of GTS include nausea, vomiting, weakness, dizziness, stomach cramps, difficulty breathing, excessive sweating, headache, and fluctuations in blood pressure and heart rate, and can last from 12 to 48 hours.2

Personal protective equipment (PPE) in tobacco-farming refers to any clothes, materials, or devices that provide protection from exposure to CPA and GTS during specific activities throughout the crop cycle.3

1 Source: Global Living Wage Coalition (GLWC)

2 Reference: Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM (September– October 2009). “Nicotinic plant poisoning.” Clinical Toxicology. 47 (8): 771–81. Doi: 10.1080/15563650903252186.

3 Adapted from the FAO/WHO (2014) International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management.

This online supplement to our integrated report should be read in conjunction with PMI’s Integrated Report 2019. The information and data presented in this online supplement cover the 2019 calendar year or reflect status at December 31, 2019, worldwide, unless otherwise indicated. Where not specified, data come from PMI estimates. See About this online supplement for more information. Aspirational targets and goals do not constitute financial projections, and achievement of future results is subject to risks, uncertainties and inaccurate assumptions, as outlined in our forward-looking and cautionary statements.